Portrait of Andre Pangrazio by Merran Koren

Andre Peter Pangrazio born 1993. Growing up in Warrnambool Andre started playing guitar and creating his own compositions when about 12 years old. His later works represent an amalgam of experiences with other young musicians as he continues to experiment with melody and time. To give the pieces shape, Andre weaves his own created narratives and utilises the many textures within the guitar and other instruments. Andre’s music creates a continuum between diverse emotions. The absence of lyrics allows listeners to explore their own journey. An exciting artistic experience. Recently Andre was chosen as an emerging Composer by Screen Works Australia. He is being mentored by Petra Salsjo, Composer and classical Pianists in Melbourne.

Portrait of Bill Struth by Jo Merriman

Bill Struth (aka Peter or Snorky) is a longstanding volunteer at basketball and football clubs and currently at local community radio station 3WAY-FM. Bill has an unbroken 27 years of service at 3WAY-FM, as a program presenter, committee member and President of the station. He has quietly gone about these roles and has contributed fully by fundraising and training/mentoring new volunteers for the station’s programs. Bill comes from generations of community minded citizens: his great, great grandfather Alexander was a local pioneer and his grandfather Alex Struth was Warrnambool Mayor (1953). Bill is a loved and respected community member and all round lovely bloke!

Bill Struth (aka Peter or Snorky) is a longstanding volunteer at basketball and football clubs and currently at local community radio station 3WAY-FM. Bill has an unbroken 27 years of service at 3WAY-FM, as a program presenter, committee member and President of the station. He has quietly gone about these roles and has contributed fully by fundraising and training/mentoring new volunteers for the station’s programs. Bill comes from generations of community minded citizens: his great, great grandfather Alexander was a local pioneer and his grandfather Alex Struth was Warrnambool Mayor (1953). Bill is a loved and respected community member and all round lovely bloke!

Portrait of Des Bunyon by Karen Richards

Des Bunyon is simultaneously a quiet force and a harmony for Warrnambool. His contributions are many and likely far more than anyone knows. Des is an adventurer, musician, visual artist, film lover, art curator, working bee contributor, artist, pet lover, art collector, song writer, advocate, enthusiast and behind the scenes contributor as well as life partner to the similarly wonderful Helen. Des can be found at openings, performances, film, markets and community consultations. His friendly smile and enchanting stories are a welcome encounter. His presence and beautiful singing voice weave this place together.

Des Bunyon is simultaneously a quiet force and a harmony for Warrnambool. His contributions are many and likely far more than anyone knows. Des is an adventurer, musician, visual artist, film lover, art curator, working bee contributor, artist, pet lover, art collector, song writer, advocate, enthusiast and behind the scenes contributor as well as life partner to the similarly wonderful Helen. Des can be found at openings, performances, film, markets and community consultations. His friendly smile and enchanting stories are a welcome encounter. His presence and beautiful singing voice weave this place together.

Portrait of Didirri Peters by Rachael Robb

Music can give us the means to connect with others, to articulate our emotions and help us shape the narrative of our lives. Didirri’s contribution to the South West and beyond is more than cultural, it is also as an artist who is unafraid, honestly exploring challenging themes whilst remaining humble and relatable. A difficult undertaking and so needed especially now. Despite music being integral to us individually and collectively its contribution to society is still vastly undervalued. Nonetheless, artists like Didirri will keep creating music, as conduits their songs gift us the means to remember who we are.

Music can give us the means to connect with others, to articulate our emotions and help us shape the narrative of our lives. Didirri’s contribution to the South West and beyond is more than cultural, it is also as an artist who is unafraid, honestly exploring challenging themes whilst remaining humble and relatable. A difficult undertaking and so needed especially now. Despite music being integral to us individually and collectively its contribution to society is still vastly undervalued. Nonetheless, artists like Didirri will keep creating music, as conduits their songs gift us the means to remember who we are.

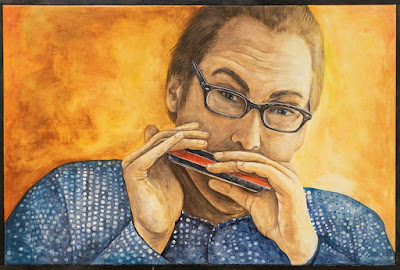

portrait of Eddy Boyle by Jenni Larsen

Eddy Boyle has accomplished more in 30 years than many people do in a lifetime. He’s been playing harmonica since he was four, influenced by his grandfather. The many highlights in his career so far include: performing at festivals and venues around the country, releasing two albums of original tracks, television appearances, teaming with artists like Chris Wilson, Joe Camilleri and more. His musical knowledge is incredible! Ask him anything about the blues and he’ll give you every detail off the top of his head! His passion is evident in his music and it’s exciting to watch him in action.

Portrait of Tom Richardson by James Chapman

Tom is a remarkable human. Tom’s impact on not only SW Victoria but several communities around the world is no less than colossal. Whilst donning several hats, Tom is a fulltime independent singer-songwriter. Tom is also the musical director and co-founder of the Find Your Voice All Abilities Choir and sits alongside wife Kim influencing the lives of many through the ground breaking True Spirit Revival. Tom is a carer, advocate, yogi, choir master and coffee addict. As Tom’s website suggests he is “your newest oldest friend” and all that know him will attest to the trueness of those words.